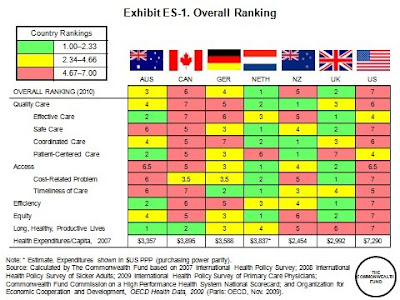

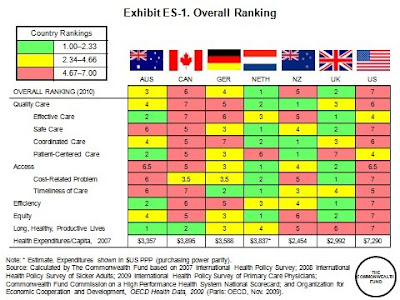

A new Commonwealth Fund study reports that

despite having the "most costly health system in the world, the United States consistently underperforms on most dimensions of performance... Compared with six other nations—Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom — the U.S. health care system ranks last or next-to-last on five dimensions of a high performance health system: quality, access, efficiency, equity, and healthy lives."

"The most notable way the U.S. differs from other countries is the absence of universal health insurance coverage. Health reform legislation recently signed into law by President Barack Obama should begin to improve the affordability of insurance and access to care when fully implemented in 2014. Other nations ensure the accessibility of care through universal health insurance systems and through better ties between patients and the physician practices that serve as their long-term “medical homes.” Without reform, it is not surprising that the U.S. currently underperforms relative to other countries on measures of access to care and equity in health care between populations with above-average and below-average incomes.

But even when access and equity measures are not considered, the U.S. ranks behind most of the other countries on most measures. With the inclusion of primary care physician survey data in the analysis, it is apparent that the U.S. is lagging in adoption of national policies that promote primary care, quality improvement, and information technology. Health reform legislation addresses these deficiencies; for instance, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act signed by President Obama in February 2009 included approximately $19 billion to expand the use of health information technology. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 also will work toward realigning providers’ financial incentives, encouraging more efficient organization and delivery of health care, and investing in preventive and population health.

For all countries, responses indicate room for improvement. Yet, the other six countries spend considerably less on health care per person and as a percent of gross domestic product than does the United States. These findings indicate that, from the perspectives of both physicians and patients, the U.S. health care system could do much better in achieving value for the nation’s substantial investment in health.

Key Findings

Quality: The indicators of quality were grouped into four categories: effective care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient-centered care. Compared with the other six countries, the U.S. fares best on provision and receipt of preventive and patient-centered care. However, its low scores on chronic care management and safe, coordinated care pull its overall quality score down. Other countries are further along than the U.S. in using information technology and managing chronic conditions. Information systems in countries like Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. enhance the ability of physicians to identify and monitor patients with chronic conditions.

Access: Not surprisingly—given the absence of universal coverage—people in the U.S. go without needed health care because of cost more often than people do in the other countries. Americans with health problems were the most likely to say they had access issues related to cost, but if insured, patients in the U.S. have rapid access to specialized health care services. In other countries, like the U.K. and Canada, patients have little to no financial burden, but experience wait times for such specialized services. There is a frequent misperception that such tradeoffs are inevitable; but patients in the Netherlands and Germany have quick access to specialty services and face little out-of-pocket costs. Canada, Australia, and the U.S. rank lowest on overall accessibility of appointments with primary care physicians.

Efficiency: On indicators of efficiency, the U.S. ranks last among the seven countries, with the U.K. and Australia ranking first and second, respectively. The U.S. has poor performance on measures of national health expenditures and administrative costs as well as on measures of the use of information technology, rehospitalization, and duplicative medical testing. Sicker survey respondents in Germany and the Netherlands are less likely to visit the emergency room for a condition that could have been treated by a regular doctor, had one been available.

Equity: The U.S. ranks a clear last on nearly all measures of equity. Americans with below-average incomes were much more likely than their counterparts in other countries to report not visiting a physician when sick, not getting a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up care, not filling a prescription, or not seeing a dentist when needed because of costs. On each of these indicators, nearly half of lower-income adults in the U.S. said they went without needed care because of costs in the past year.

Long, healthy, and productive lives: The U.S. ranks last overall with poor scores on all three indicators of long, healthy, and productive lives. The U.S. and U.K. had much higher death rates in 2003 from conditions amenable to medical care than some of the other countries, e.g., rates 25 percent to 50 percent higher than Canada and Australia. Overall, Australia ranks highest on healthy lives, scoring in the top three on all of the indicators."