Thursday, May 28, 2009

Health Wonk Review is up at Boston Health News

Healthcare Technology News is featured for its article on the health industry's meeting with President Obama.

Also highlighted: a look at HealthSouth's failed Digital Hospital initiative, which now is just an empty building. "So we have gone from 'the hospital model for the world,' with great 'promise,' which 'could save lives,' proclaiming the 'era of cyber hospitals,' to a 'pipe dream,' just the shell of half-finished building."

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

Mark Leavitt Snaps (Back)

So enough is enough. Leavitt feels he's been on the hot seat and responds in a piece entitled "Certifying Health IT: Let's Set the (Electronic Health) Record Straight". Leavitt spends a paragraph listing CCHIT Commissioners chronologically one-by-one to make the case that CCHIT is not, as suggested by Kibbe, a “vendor-founded, -funded and -driven organization.”

So enough is enough. Leavitt feels he's been on the hot seat and responds in a piece entitled "Certifying Health IT: Let's Set the (Electronic Health) Record Straight". Leavitt spends a paragraph listing CCHIT Commissioners chronologically one-by-one to make the case that CCHIT is not, as suggested by Kibbe, a “vendor-founded, -funded and -driven organization.”In an unusual combination of third person narrative, followed by direct first person assault, Leavitt asks Kibbe: "In support of this heartfelt concern for transparency, could you arrange for the Washington Post to append to your statements a disclosure of any possible conflicts of interest you might have? Such as financial relationships with companies that market health IT products or services? I have none."

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology is nearing a decision on the certification organization for electronic health records. This organization will be responsible for ensuring that the ARRA stimulus billions will be well spent by U.S. health care organizations on systems that can deliver real meaningful use of electronic health records. CCHIT had been viewed by many as the "heir apparent" for this role.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Blog Rally: Raising Awareness for Public Participation in Healthcare X PRIZE Development

Blog Rally (b’lôg răl’ē) adj.

1. A coordinated, simultaneous presentation of identical or similar material on numerous blogs for the purpose of engaging large numbers of readers and/or persuading them to adopt a certain position or take a certain action.

2. The simultaneous nature of a blog rally can create the result of joining the efforts of otherwise independent bloggers for an agreed-upon purpose.

We are entering an unprecedented season of change for the United States health care system. Americans are united by their desire to fundamentally reform our current system into one that delivers on the promise of freedom, equity, and best outcomes for best value. In this season of reform, we will see all kinds of ideas presented from all across the political spectrum. Many of these ideas will be prescriptive, and don’t harness the power of innovation to create the dramatic breakthroughs required to create a next generation health system.

We believe there is a better way.

This belief is founded in the idea that aligned incentives can be a powerful way to spur innovation and seek breakthrough ideas from the most unlikely sources. Many of the reform ideas being put forward may not include some of the best thinking, the collective experience, and the most meaningful ways to truly implement change. To address this issue, the X PRIZE Foundation, along with WellPoint Inc and WellPoint Foundation as sponsor, has introduced a $10MM prize for health care innovators to implement a new model of health. The focus of the prize is to increase health care value by 50% in a 10,000 person community over a three year period.

The Healthcare X PRIZE team has released an Initial Prize Design and is actively seeking public comment. We are hoping, and encouraging everyone at every opportunity, to engage in this effort to help design a system of care that can produce dramatic breakthroughs at both an individual vitality and community health level.

Here is your opportunity to contribute:

1. Download the Initial Prize Design

2. Share you comments regarding the prize concept, the measurement framework, and the likelihood of this prize to impact health and health care reform.

3. Share the Initial Prize Design document with as many of your health, innovation, design, technology, academic, business, political, and patient friends as you can to provide an opportunity for their participation

We hope this blog rally amplifies our efforts to solicit feedback from every source possible as we understand that innovation does not always have a corporate address. We hope your engagement starts a viral movement of interest driven by individual people who realize their voice can and must be included. Let’s ensure that all of us – and the people we love – can have a health system that aligns health finance, care delivery, and individual incentives in a way that optimizes individual vitality and community health. Together, we can ensure the best ideas are able to come forward in a transparent competition designed to accelerate health innovation. We look forward to your participation.

Special thanks to Paul Levy for both demonstrating the value of collaborative effort and suggesting we utilize a blog rally for this crowdsourcing effort.

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

Grand Rounds

Type 1 diabetic for over 22 years, blogger Kerri Sparling says it all in her post at Six Until Me:

"Why, Insurance Company, are you so against proactive care? Why do I need to pay more for a brace or a shot or an extra visit when you're more content paying for a several thousand dollar surgery instead? Not enough bang for your buck? Why do you fight me tooth and nail against coverage for a continuous glucose monitoring device? Is my life not worth the investment to keep my legs on instead of paying 100% to amputate them in a few decades? I know I'm expensive as a chronic disease patient, but I'm healthier than 85% of the people I know. I eat well, I exercise regularly, and I am on top of my disease. Yet you deny me life insurance, you won't let me purchase a private health insurance policy, and you would rather see me on an operating table than taking up a doctor's time in an office visit. (And it's not like I'm taking up more than 5 - 7 minutes of a doctor's time, because that's about all we get, on average. Pathetic.)"

"Why, Insurance Company, are you so against proactive care? Why do I need to pay more for a brace or a shot or an extra visit when you're more content paying for a several thousand dollar surgery instead? Not enough bang for your buck? Why do you fight me tooth and nail against coverage for a continuous glucose monitoring device? Is my life not worth the investment to keep my legs on instead of paying 100% to amputate them in a few decades? I know I'm expensive as a chronic disease patient, but I'm healthier than 85% of the people I know. I eat well, I exercise regularly, and I am on top of my disease. Yet you deny me life insurance, you won't let me purchase a private health insurance policy, and you would rather see me on an operating table than taking up a doctor's time in an office visit. (And it's not like I'm taking up more than 5 - 7 minutes of a doctor's time, because that's about all we get, on average. Pathetic.)" Laurie Edwards at A Chronic Dose reviews "Are We Feeling Better Yet?" a collection of essays from prominent women writers that speak to challenges and contradictions in our current system. While she found that no, we aren't necessarily getting better yet, the stories show where we need to go. Edwards argues that the patient narrative deserves a place in the reform conversation.

Laurie Edwards at A Chronic Dose reviews "Are We Feeling Better Yet?" a collection of essays from prominent women writers that speak to challenges and contradictions in our current system. While she found that no, we aren't necessarily getting better yet, the stories show where we need to go. Edwards argues that the patient narrative deserves a place in the reform conversation.

Robin S at Survive the Journey details the challenges of access based on socioeconomic and racial factors. A Johns Hopkins study found that socioeconomic and racial factors are predictors to admission for pituitary adenoma patients to high-quality care centers. " The number of patients receiving care in the >$60,000/yr income-bracket was almost double the other income levels."

Robin S at Survive the Journey details the challenges of access based on socioeconomic and racial factors. A Johns Hopkins study found that socioeconomic and racial factors are predictors to admission for pituitary adenoma patients to high-quality care centers. " The number of patients receiving care in the >$60,000/yr income-bracket was almost double the other income levels."

Jane Sarasohn-Kahn at Health Populi lays out the costs of chronic disease and the key role of self-care.

Stacey Butterfield at ACP Internist finds that health care reform starts at home, as physicians at one conference practice what they preach when it comes to preventive medicine.

Nancy Brown at Teen Health 411 finds that primary care physicians could do more to screen for teen eating disorders to avoid hospitalizations.

John Halamka at Life as a Healthcare CIO describes the first meeting of the ARRA/HITECH mandated HIT Standards Committee which focused on the following key themes:

"a. We need a high level roadmap of milestones to ensure we meet our statuary deadlines for initial deliverables in time for the 12/31/09 interim rule.

b. We also need a roadmap which takes into account the other mandates/compliance requirements already imposed on healthcare stakeholders such as ICD-10 and X12 5010. We need to ensure our clinical work is in synch with administrative data exchange activities already in progress.

c. Although we should provide for the exchange of basic text, we should strive for semantic interoperability whenever possible, using controlled vocabularies which are foundational to decision support and quality reporting.

d. We should set the bar for interoperability higher than the status quo but also make it achievable, realizing that rural providers and small clinician offices have less capabilities than large academic health centers. We'll need to retrofit many existing systems - healthcare IT is not a greenfield and thus we need to be realistic about the capabilities of existing software, while also encouraging forward progress and innovation.

e. Meaningful use will change over time. Data exchange and the standards we select must evolve. To ensure successful adoption throughout the industry, our work must be continuous incremental progress with phased adoption of standards."

Barbara Olson at On Your Meds discusses what "meaningful use" may mean for medication safety. She advocates for making medication histories and profiles of patients accurate and readily accessible across the continuum of care are among the most important targets for “meaningful use” initiatives.

Mr. HIStalk reports on the ONC's plans to define “meaningful use”. "Translation: we haven’t figured out what we are doing yet and aren’t ready to commit to anything."

Wes Rishel at the Gartner found that the successful EHR implementations included health information exchange and used "implementation approaches that are more highly directive and more keyed to supporting the practices' complete workflow changes necessary to benefit from the EHR."

Health Business Blog's David Williams interviews EHR vendor Practice Fusion's CEO, Ryan Howard.

Laika Spoetnik's MedLibLog gives an example of a real successful application of web 2.0 in patient centered healthcare for Parkinson's disease. Health 2.0 represents "a new way of thinking in healthcare:

- the patient becomes centric, care becomes collaborative: the patient is not passive, he is “equal” to the healthcare provider. It isn’t “he asks, we provide”, but the patient definitively has a voice (and choice) in his own healthcare.

- coherent and transparent healthcare.

- expertise (few experts, but with very specialized knowledge)."

DrRich at the Covert Rationing Blog explains why the representatives of all the major healthcare interests threw in with President Obama's healthcare reform. DrRich believes that this time is different than the Clintons' attempt in '93. "The private concerns, this time, have shot their wad. They are entirely bereft of ideas. They know not what to do... And so, the last obstruction to healthcare reform has been removed."

Bob Laszewski at Healthcare Policy and Marketplace Review sends out an open letter to the Congressional Budget Office. "So, six months later lawmakers are sending one of these "cost containment lite" proposals after another over to the the CBO and the CBO is sending them back stamped, "insufficient funds." And there's lots of whining about it now going on atop the Hill where people are desperate to find easy money for health care reform. It will take more than $1.2 trillion to pay for health care reform and the Obama budget cuts have only identified about $300 billion toward that goal. We will not reform the health care system unless we really reform the health care system. The only thing standing between BS reform and real reform are the men and women--real men and real women--over at the CBO."

Jacob Goldstein at the Health Blog highlights OMB chief Peter Orszag's comments on the four steps to better cheaper care.

Louise at Colorado Health Insurance Insider describes the House pledge to have a sweeping health care reform bill on the floor by the end of July, and the details starting to come out about the direction they want to take. Requiring everyone to have health insurance coverage is one of the cornerstones of the reform.

Bob Vineyard at Insure Blog argues against the hidden costs of health care reform.

Alison Finney at Shoot Up or Put Up (Comatose and rotting toes - the lighter side of insulin dependency), was diagnosed with Type One Diabetes in 1983 at the age of 4. She gets her healthcare from the UK's National Health Service. While the British NHS may have it's faults, as a patient with a chronic disease she's a real fan.

Passing the Baton

Next week's Grand Rounds will be hosted by See First. Check out Evan Falchuk's See First article on the language of health care reform. Does it reveal a "deepening divide between how people talk about health care and what it really means to be sick"?

Next week's Grand Rounds will be hosted by See First. Check out Evan Falchuk's See First article on the language of health care reform. Does it reveal a "deepening divide between how people talk about health care and what it really means to be sick"?

Check in at Get Better Health for the Grand Rounds schedule. Thanks to Val Jones and Colin Son for organizing Grand Rounds.

Friday, May 15, 2009

HITECH Interoperetta

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

'What we call health care costs, they call income'

Insurance companies, hospitals, physicians, pharma and labor organizations are supporting this voluntary plan in the hopes of fending off legislation that controls costs. The groups include the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, America’s Health Insurance Plans, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the Advanced Medical Technology Association, and the Service Employees International Union.

According to Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar and Philip Elliott, "it's unclear whether the proposed savings will prove decisive in pushing a health care overhaul through Congress. There's no detail on how the savings pledge would be enforced. And, critically, the promised savings in private health care costs would accrue to society as a whole, not just the federal government. That's a crucial distinction because specific federal savings are needed to help pay for the cost of expanding coverage."

President Obama's stated that "we cannot continue down the same dangerous road we've been traveling for so many years, with costs that are out of control, because reform is not a luxury that can be postponed, but a necessity that cannot wait... It is a recognition that the fictional television couple, Harry and Louise, who became the iconic faces of those who opposed health care reform in the ⿿90s, desperately need health care reform in 2009. And so does America... That is why these groups are voluntarily coming together to make an unprecedented commitment. Over the next ten years - from 2010 to 2019 - they are pledging to cut the growth rate of national health care spending by 1.5 percentage points each year - an amount that's equal to over $2 trillion."

Janet Adamy of The Wall Street Journal reports that "administration officials said, they do not have a way to enforce the commitment, other than by publicizing the performance of health care providers to hold them accountable. By offering to hold down costs voluntarily, providers said, they hope to stave off new government price constraints that might be imposed by Congress or a National Health Board of the kind favored by many Democrats."

Janet Adamy of The Wall Street Journal reports that "administration officials said, they do not have a way to enforce the commitment, other than by publicizing the performance of health care providers to hold them accountable. By offering to hold down costs voluntarily, providers said, they hope to stave off new government price constraints that might be imposed by Congress or a National Health Board of the kind favored by many Democrats."

Jeffrey Young at The Hill.com reported that this commitment would "translate into annual savings of $2,500 for a family of four after five years. Over time, slowing the growth of healthcare spending at this rate would 'virtually eliminate the nation’s long-term fiscal gap.'"

But will these trade associations still be on board with the Tom Daschle's view that "a public plan will reduce costs and improve access"? "Employer premiums could be substantially lowered with the choice of a public health-insurance plan; a typical American family could save nearly $1,000 a year in reduced premiums alone. If containing costs is one of our biggest goals, how can we not do this?"

Monday, May 11, 2009

Healthcare Information Technology Expert Panel

The Healthcare Information Technology Expert Panel II by John Halamka

Last week, I joined an amazing group of colleagues at the National Quality Forum's Healthcare Information Technology Expert Panel to work on a next generation quality data set. They key breakthrough was the development of a universal terminology for the design of quality measures which captures process and outcome data from electronic systems.

Last week, I joined an amazing group of colleagues at the National Quality Forum's Healthcare Information Technology Expert Panel to work on a next generation quality data set. They key breakthrough was the development of a universal terminology for the design of quality measures which captures process and outcome data from electronic systems.Elements which are captured include:

Datatype (e.g., medication order)

Data (e.g., aspirin)

Attributes (e.g., date/time)

Data Source (e.g., physician, patient, lab)

Data Recorder (e.g., physician, lab, monitor)

Data Setting (e.g., home, hospital, rehab facility)

Health Record Field (e.g., problem list, med list, allergy)

In the original HITEP work last year, 35 datatypes were defined such as encounter, diagnosis, diagnostic study, laboratory, device, intervention, medication, symptom etc. Each datatype can have subtypes describing specific events. Here's an example of the subtypes of the medication datatype

medication administered

medication adverse event

medication allergy

medication discontinued

medication dispensed

medication intolerance

medication order

medication prescribed

medication offered

medication refused

A traditional measure of quality might be

"Was Aspirin administered within 5 minutes of ED arrival in diagnosis of acute MI?"

If an EHR transmits datatypes for encounter, diagnosis, and medication to a quality data warehouse, we could capture the following data:

Datatype - encounter

Data - ED arrival

Attribute - date/time of arrival

Source - registration system

Recorder - ED ward clerk

Setting - ED

Health record field - ED arrival date/time

Datatype - diagnosis

Data - MI

Codelist - SNOMED code 12345

Attribute - date/time of diagnosis

Source - physician

Recorder - physician

Setting - ED

Health record field - encounter diagnosis

Datatype - medication administered

Data - ASA

Codelist - RxNorm code 123456

Attribute - date/time of administration

Source - nurse

Recorder - nurse

Setting - ED

Health record field - medication administered

then the quality measure could be defined as

Diagnosis="SNOMED 12345" AND (medication administered="RxNorm 123456" date/time - ED arrival encounter date/time) < 5 minutes

Such an approach makes quality measures more clearly defined, more directly related to data elements in EHRs, and more easily maintained.

The next steps for NQF include review of their existing 500 quality measures to determine which could be placed into such a framework. If there are gaps or revisions needed, the NQF will work with quality measure development organizations.

Meaningful use of EHRs will likely include quality measurement. Having a framework for recording quality data and computing measures is foundational.

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Totally Off Topic - Wanda Sykes

Saturday, May 9, 2009

HIT Standards Committee Named

Jonathan Perlin, M.D., Chair

Jonathan Perlin, M.D., Chair

Healthcare Corporation of America

John Halamka, M.D., Co-Chair

John Halamka, M.D., Co-Chair

Harvard Medical School

Dixie Baker, Ph.D.

Science Applications International Corporation

Anne Castro

BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina

Christopher Chute, M.D.

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine

Janet Corrigan, Ph.D.

National Quality Forum

John Derr, R.Ph.

Golden Living, LLC

Linda Dillman

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.

James Ferguson

Kaiser Permanente

Steven Findlay, M.P.H.

Consumers Union

Douglas Fridsma, M.D., Ph.D.

Arizona Biomedical Collaborative

C. Martin Harris, M.D., M.B.A.

Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Stanley M. Huff, M.D.

Intermountain Healthcare

Kevin Hutchinson

Prematics, Inc.

Elizabeth O. Johnson, R.N.

Tenet Health

John Klimek, R.Ph.

National Council for Prescription Drug Programs

David McCallie, Jr., M.D.

Cerner Corporation

Judy Murphy, R.N.

Aurora Health Care

J. Marc Overhage, M.D., Ph.D.

Regenstrief Institute

Gina Perez, M.P.A.

Delaware Health Information Network

Wes Rishel

Gartner, Inc.

Sharon Terry, M.A.

Genetic Alliance

James Walker, M.D.

Geisinger Health System

Thursday, May 7, 2009

The Week in Review - May 7, 2009

NCVHS hears from leaders on the definition of meaningful use including physicians, the Markle Foundation (and 60 supporting organizations), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), College of Healthcare Information Management Executives (CHIME), American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA), HIMSS and a broad range of other industry leaders. Carolyn Clancy, AHRQ Director, says that healthcare organizations should prepare now by using health registries to manage the health information of patients with chronic diseases.

Wall Street Journal reports on an "affordable fix for modernizing medical records", the VA's Vista system.

Wall Street Journal reports on an "affordable fix for modernizing medical records", the VA's Vista system.Dr. David Blumenthal, National Coordinator for Health IT, believes that healthcare technology has not advanced sufficiently "when left exclusively to the private sector, so there is a public role."

American Public Media's Markeplace reports that investment in "health care information technology is holding its own. Investors are following the $20 billion in President Obama's stimulus plan to upgrade and modernize health records."

The Use of Health IT in Crisis Control interviews Dr. Nathaniel Hupert, Director of The Preparedness Modeling Unit for The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Associate Professor of public health and medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College.

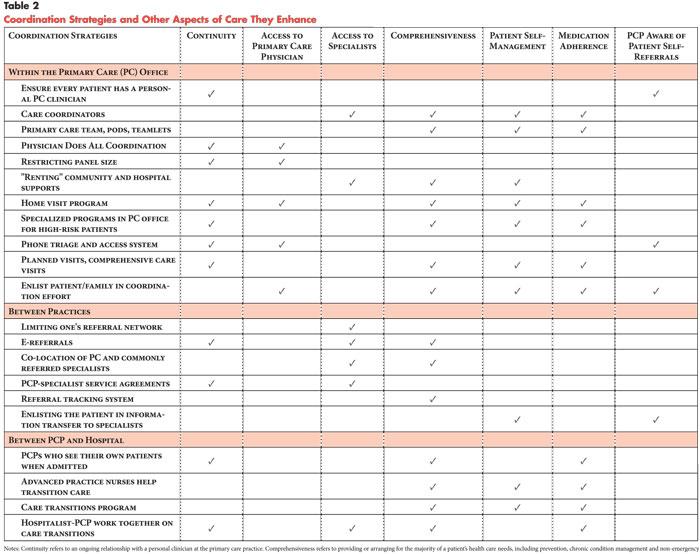

Coordination of Care by Primary Care Practices: Strategies, Lessons and Implications reports that "while there was no single recipe for coordination ... some cross-cutting lessons were identified, such as the value of a commitment to interpersonal continuity of care as a foundation for coordination." Medical home initiatives "if aligned with payment incentives ... have the potential to increase quality and satisfaction among patients and providers by helping to move the health care delivery system toward better coordinated care."

Coordination of Care by Primary Care Practices: Strategies, Lessons and Implications reports that "while there was no single recipe for coordination ... some cross-cutting lessons were identified, such as the value of a commitment to interpersonal continuity of care as a foundation for coordination." Medical home initiatives "if aligned with payment incentives ... have the potential to increase quality and satisfaction among patients and providers by helping to move the health care delivery system toward better coordinated care."Archives of Internal Medicine reports that "computerized medication reconciliation tool and process redesign were associated with a decrease in unintentional medication discrepancies with potential for patient harm. Software integration issues are likely important for successful implementation of computerized medication reconciliation tools."

Health Care Policy and Marketplace Review has maintained a laser focus on the need for healthcare reform to result in real savings. In his latest post, Bob Laszewski contends that "health care reform means fixing the system so we stop spending/wasting so much more than every other industrial nation on health care thereby making our system more affordable and effective." In earlier posts, he referenced two December 2008 CBO reports on the potential savings associated with various reform programs: Key Issues in Analyzing Major Health Insurance Proposals and Budget Options Volume 1 Health Care. "If the CBO just rolls over and lets Congress make up excuses just to spend more for health care we will not have reform--we will only have a bigger fiscal disaster on our hands. How do you reform entitlements by pretending?"

The AMA announces initial partner agreements to provide a secure AMA portal offering a variety of practice management services.

Computer modeling predicts the spread of swine flu. One of the algorithms is rooted in human contact models derived from Where's George? which tracks the passage of one dollar bills from person to person.

HealthMap provides a global disease alert map, including tracking of swine

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

Chronic Care: Best Practices for Care Coordination

Randy Brown graciously took the time to sit down with Healthcare Technology News to discuss his findings regarding "Models that Decrease Hospitalizations and Improve Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Illnesses" (links here to executive summary and full report).

Randy Brown graciously took the time to sit down with Healthcare Technology News to discuss his findings regarding "Models that Decrease Hospitalizations and Improve Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Illnesses" (links here to executive summary and full report).HTN: Many physicians all share one common complaint: that the way care is delivered today is incredibly fragmented. Can you give us some idea of the magnitude of the problem?

Randy Brown: Mai Pham, a colleague of mine at a Mathematica subsidiary, the Center for Health Care Strategies, has done some very interesting work that illustrates the difficult, seemingly impossible, task that physicians face in trying to coordinate the care of their patients. First, she showed that the typical (median) Medicare beneficiary with chronic illnesses saw 7 different physicians during the course of a year. This does not include non-MD medical professionals at skilled nursing facilities or home health agencies who treated the patient. We have done some work of our own and found even higher numbers of physicians seeing a given patient with Congestive Heart Failure (CHF), Coronary Artery Disease (CAD), or diabetes—our estimate was 12 physicians. Gerry Anderson at Hopkins had a similar estimate.

Dr. Pham also looked at it from the doctor’s perspective across the full case load they have and found some startling numbers—her research showed that the median number of different physicians seen by a given physician’s Medicare patients during the course of a year is 229. That means a typical physician would need to coordinate with 229 different physicians during the course of a year (just for their Medicare patients), with many of these requiring multiple contacts because they see the physician’s patients multiple times throughout the year.

These hard data illustrate just how fragmented care is, and what a monumental task it would be for physicians to coordinate it on their own.

HTN: You looked at many different models to coordinate care. What were the keys to success?

Randy Brown: Across a range of rigorous studies we examined or conducted ourselves, we found some common features among the most successful programs. Most of our inferences were drawn from about 20 demonstration programs we have evaluated. Unsuccessful programs also had some of these features, but not all of them, and in some cases didn’t implement them as intensively. Here’s what we found: First, in the successful programs the care coordinators saw patients in-person fairly frequently—about once a month actually—in addition to telephonic contacts. Second, the successful programs targeted people with a substantial risk of hospitalization in the coming year. Third, care coordinators were co-located with the patients’ primary physicians, so they knew and trusted each other, and had frequent opportunities for interacting informally and exchanging information on a patient. Fourth, the successful programs tried to assign the same care coordinator to all of a physician’s patients in the program, to minimize the number of different people the physician had to interact with, and to build trust and familiarity. Fifth, the most effective programs had timely information on when patients were admitted to a hospital, so they could quickly begin working on the new needs the patient would have and capitalize on the learning opportunity presented by the crisis that got them admitted to the hospital. Sixth, the most effective models had the most well-designed and implemented patient education interventions of the programs we evaluated. And last but not least, the two most successful programs were (with one exception) the only ones out of 12 programs for which we had survey data for which the proportion of treatment group patients reporting someone had taught them how to take their medications correctly was significantly higher than the proportion of the corresponding control group reporting they received such guidance.

HTN: What were some of the metrics that defined success?

Randy Brown: We defined “success” as a program that reduced hospitalizations or reduced Medicare expenditures, over a followup period of at least one year. We did not count as successes programs that only improved clinical indicators or patient satisfaction. While these types of improvements are obviously important, settling for only those types of gains would be setting the bar too low. We can and we should reduce the high rate of preventable hospitalizations.

HTN: What innovations did you find in the enabling technologies that seem promising?

Randy Brown: Actually, we found nothing in the way of technologies that distinguished successful from unsuccessful programs. That’s not to say that having EMRs or PHRs would be a waste of money; clearly, it would be helpful for all providers to be able to see a patient’s test results and recent visits and other physicians’ notes about the patient. But it wasn’t the factor that distinguished the successful and unsuccessful programs in our studies or others I’ve seen. That may be because few of the programs really had strong EHRs.

Some of the programs used heart monitors or home reporting devices for some of their patients. But again, we found no strong association between such innovations and outcomes. Other unpublished work I’ve seen suggests that there may be some potential there, but it remains to be proven in rigorous trials.

HTN: What are the possibilities and limitations of the Patient Centered Medical Home?

Randy Brown: Medical homes have a number of features that we find are associated with successful care coordination—in-person contacts between care coordinators and patients, co-location of care coordinators and patients’ physicians, and care coordinators potentially having access to timely information on when patients are admitted to a hospital or emergency room. But two issues could limit their effectiveness. First, medical homes will need to reflect some of the other lessons learned about what constitutes effective care coordination as well, like the need for a strong educational intervention (especially around how to take their medications properly), effective monitoring of patients between office visits, a patient-centered focus, teaching patients (and/or their caregivers) how to self-manage their care, effective care planning, and availability of social supports to identify and address problems of depression, isolation, and unmet needs for basic goods and services like transportation or food. Yet these are not required features of a medical home. And even if they were, practices need to know how to implement these factors into their medical home interventions in ways that will be both efficacious and efficient. The second major problem with medical homes as currently designed is targeting. Practices participating in CMS’s medical home demonstration will receive monthly fees for virtually all of their Medicare patients. While all patients should have a usual source of care, many do not need the medical home level of intensity. The diffusion of effort and payment makes it virtually certain that the intervention will not generate net savings, and may not even generate some gross savings in Medicare expenditures before fees. It would seem to be more important to focus efforts and resources on the 20 percent or so of patients who really are at high risk of hospitalization, and really need a medical home level of engagement. That could be made clear to practices by restricting medical home payments to patients who met those criteria (and making that rate higher than the highest of the 4 categories currently planned).

HTN: There are so many physicians practicing in small groups that are challenged to coordinate care. What do they do?

Randy Brown: Good question. About 45 percent of all physicians in the country practice solo or with one other physician. There’s no way they have the scale of operations to meet the criteria to be a medical home on their own, or to provide care coordination services, which are not covered by Medicare. But if a tightly defined care coordination benefit were covered by Medicare, they could get such services for their patients from a local hospital, academic medical center, home health agency, or clinic that decided to offer such a program to any patient in the community who met the eligibility criteria. North Carolina has a program like this.

HTN: Tell us about CMS’s Care Transitions Project.

Randy Brown: This new project was just announced by CMS a few weeks ago, on April 13. Essentially, the QIOs (Quality Improvement Organizations) are tasked with providing assistance to 14 communities around the country to help them reduce their hospital readmission rates, and improve transitions between various types of settings (hospitals, nursing facilities, rehab hospitals, home health care). Nationally, 18% of all Medicare beneficiaries who are admitted to a hospital are readmitted within 30 days after discharge, and three-fourths of these readmits are for preventable reasons. Patients are discharged to home not fully understanding the self-care they are supposed to practice, their new medication regimen, the diet they are supposed to adhere to, what activity level is recommended for them and when they can increase it, symptoms that could indicate a possible problem for which they should be seen immediately, or the importance of making and keeping a followup appointment. At the time they are discharged, they and their family caregivers are confused and bombarded with information, of which they often absorb very little. Transitional care programs, such as those developed by Mary Naylor at University of Pennsylvania school of nursing or Eric Coleman at the University of Colorado, are designed to help patients overcome these problems. They’ve been shown to be very successful in reducing readmissions for patients with chronic illnesses, in well-designed clinical trials.

The idea of the Care Transitions program is to help communities develop solutions that address the factors that lead to high hospital readmissions in their own environment—it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution across the country. The QIO’s will have Care Transitions experts in each of the 14 communities who will organize these efforts. While this idea might not have been too attractive to hospitals in the past, because it would result in lost revenue from those readmissions, President Obama has proposed new rules that would no longer reward hospitals for unplanned readmissions. So the Care Transitions program may be considerably more attractive to hospitals now. You can learn more about it at the Care Transitions website.

HTN: You make the point that not only are readmissions a problem, but in many cases so are the original admission. How significant an opportunity is there for improvement?

Randy Brown: Many of the hospitalizations for patients with chronic illnesses like CHF, CAD or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) are preventable if patients received better care and more appropriate medications, and adhered better to their physician’s prescribed regimens for diet, exercise, medications and self-care. The proportion of hospitalizations that are preventable (they’re also called ambulatory sensitive conditions, because they are sometimes attributable to inadequate ambulatory care) is high, and varies across conditions. For Congestive Heart Failure, half of all hospital admissions are considered potentially preventable. Efforts to reduce preventable hospitalization across a range of conditions may be especially cost-effective as beneficiaries who had such events accounted for about 17% of all Medicare reimbursement for inpatient, outpatient, and physician services in one 1998 study (Culler, Parchman, and Przybylski). So there is substantial opportunity for reductions in these admissions among patients with serious chronic conditions, without having to wait for one to occur before you intervene. To give you another feel for the potential, we found when looking at the most successful programs in the Medicare Coordinated Care demonstration that hospitalizations for patients with heart disease were reduced by 17 percent, with essentially none of the this reduction being due to lower rates of short term readmissions.

HTN: Does talk of care coordination paper over a deeper problem with our care delivery organization and incentives?

Randy Brown: Yes, it seems pretty clear that our systems are not designed to encourage providers to minimize the need for expensive procedures. Rewards to providers are proportional to the amount of services they provide, rather than the quality and efficiency of the care they deliver. Notice that I said quality and efficiency of care—there are a number of fairly new pay-for-performance efforts out there that reward providers for improved quality, as measured by things like the proportion of their patients receiving preventive care. While improving such indicators is a good thing, it doesn’t focus on coordinating care to reduce the need for hospitalizations, which is the more urgent need and the only focus that is likely to start reducing the rate of growth of medical costs in the near term. And the example I mentioned above concerning hospitals being a bit wary of big efforts to reduce readmissions is another illustration of perverse incentives in our system. Fortunately, incentives can be changed to increase payments to providers whose patients use relatively low levels of expensive services while maintaining or improving the quality of care and patient well-being, and decreasing payments to providers whose patients use relatively high levels of such services. These payments would have to account for differences in severity of illness and comorbidities across providers, but a variety of methods for doing that exist. CMS is funding some research now to lay the groundwork for such payment methods and to disseminate information to physicians about the Medicare cost per episode of care for their own patients relative to that for similar patients seen by other physicians in the same geographic area, and to that of physicians nationally. It will be interesting to see how physicians respond to this information—they’ve never had such feedback before.

We clearly need multiple approaches to address the problems we have; there’s no single magic bullet.

HTN: It seems so obvious that “high touch” methods would be important to patient outcomes. Why is it so rarely used? And how do these best practice high touch methods differ from the services offered by disease management companies?

Randy Brown: High touch care requires a lot of labor, and labor is expensive. The nursing shortage has exacerbated the problem—experienced nurses are hard to find and costly. In our study of 15 Medicare Coordinated Care demonstration programs we found that the programs in which the care coordinators had the most frequent in person contacts tended to be the ones with the largest reductions in hospitalizations. They averaged nearly 1 in person contact per patient per month. That is in stark contrast to the almost solely telephonic contacts by most disease management companies. Those programs have long claimed that they generate large reductions in hospitalizations. Nearly all of those claims are based on deeply flawed studies. When we conducted randomized trials of these disease management programs for Medicare, we found no effects on hospitalizations for any of them. The lack of in person contacts means that the patients tend not to take the care coordinator that seriously, or trust them. It’s just a disembodied voice at the other end of the line. While the patients love the attention, the nurse care coordinator may not be getting their message across. Care coordinators whose only contact with patients is telephonic can’t see the patients’ faces or body language, to see whether they are really grasping the message; they can’t observe loose rugs in the house or the absence of grab bars in the shower or the stock of junk food on the counter or the sallow skin of a decompensating patient; and maybe most importantly, they can’t establish that trust that comes from face to face contact with a medical professional who actually lays hands on them. So the high touch approach is the only one that really seems to be effective, but it isn’t cheap. That’s why one of the biggest challenges for care coordination programs is to learn how to generate more efficiently the favorable impacts we’ve seen in the most effective programs. Since one of our goals has to be to generate some net savings for Medicare and other payers, it isn’t enough to reduce hospitalizations—we have to be able to do it in a cost-effective manner. That will require triaging patients by their level of need for intensive care coordination, and possibly discharging some; using in person contacts enough to produce the savings while not relying too heavily on them over time for all patients; and investigating the use of lower cost staff, such as LPNs and social workers for some of the care coordination work.

Bio

Randall S. Brown (Ph.D. Economics, University of Wisconsin) is a Vice President and Director of Health Research at Mathematica Policy Research in Princeton, NJ. Over the past 25 years, Dr. Brown has designed and led evaluations of some of the nation’s largest demonstration programs in both care coordination and long term care. He is currently leading several ongoing studies of these programs to develop lessons about how to improve outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic illnesses. In the long term care area, he led the evaluation of the Cash and Counseling Demonstration, for which he and his MPR colleagues won the AcademyHealth 2009 Impact Award. He currently is Principal Investigator for the Money Follows the Person program evaluation. His most prominent earlier work includes leading large-scale evaluations of the Medicare managed care program, the expansion of Medicaid benefits to low-income families, and the National Channeling Demonstration.

Monday, May 4, 2009

Red Flags Rule - Enforcement Reprieve

Most health care organizations will be covered under this rule. The AMA's Practice Management Center has published a sample policy for Red Flags compliance and a good overview document on what physician practices should do to prepare for Red Flags compliance. The AMA is taking credit for the change in the enforcement date, but has been unsuccessful in arguing its applicability to health care.

The FTC has published the following regarding medical identity theft:

The “Red Flags” Rule: What Health Care Providers Need to Know About Complying with New Requirements for Fighting Identity Theft

As many as nine million Americans have their identities stolen each year. The crime takes many forms. But when identity theft involves healthcare, the consequences can be particularly severe.

Medical identity theft happens when a person seeks healthcare using someone else’s name or insurance information. A survey conducted by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) found that close to 5% of identity theft victims have experienced some form of medical identity theft. Victims may find their benefits exhausted or face potentially life‑threatening consequences due to inaccuracies in their medical records. The cost to healthcare providers – left with unpaid bills racked up by scam artists – can be staggering, too.

The Red Flags Rule, a law the FTC will begin to enforce on August 1, 2009, requires certain businesses and organizations – including many doctor’s offices, hospitals, and other healthcare providers – to develop a written program to spot the warning signs – or “red flags” – of identity theft. Is your practice covered by the Red Flags Rule? If so, have you developed your Identity Theft Prevention Program to detect, prevent, and minimize the damage that could result from identity theft?

WHO MUST COMPLY

Every healthcare organization and practice must review its billing and payment procedures to determine if it’s covered by the Red Flags Rule. Whether the law applies to you isn’t based on your status as a healthcare provider, but rather on whether your activities fall within the law’s definition of two key terms: “creditor” and “covered account.”

Healthcare providers may be subject to the Rule if they are “creditors.” Although you may not think of your practice as a “creditor” in the traditional sense of a bank or mortgage company, the law defines “creditor” to include any entity that regularly defers payments for goods or services or arranges for the extension of credit. For example, you are a creditor if you regularly bill patients after the completion of services, including for the remainder of medical fees not reimbursed by insurance. Similarly, healthcare providers who regularly allow patients to set up payment plans after services have been rendered are creditors under the Rule. Healthcare providers are also considered creditors if they help patients get credit from other sources – for example, if they distribute and process applications for credit accounts tailored to the healthcare industry.

On the other hand, healthcare providers who require payment before or at the time of service are not creditors under the Red Flags Rule. In addition, if you accept only direct payment from Medicaid or similar programs where the patient has no responsibility for the fees, you are not a creditor. Simply accepting credit cards as a form of payment at the time of service does not make you a creditor under the Rule.

The second key term – “covered account” – is defined as a consumer account that allows multiple payments or transactions or any other account with a reasonably foreseeable risk of identity theft. The accounts you open and maintain for your patients are generally “covered accounts” under the law. If your organization or practice is a “creditor” with “covered accounts,” you must develop a written Identity Theft Prevention Program to identify and address the red flags that could indicate identity theft in those accounts.

SPOTTING RED FLAGS

The Red Flags Rule gives healthcare providers flexibility to implement a program that best suits the operation of their organization or practice, as long as it conforms to the Rule’s requirements. Your office may already have a fraud prevention or security program in place that you can use as a starting point.

If you’re covered by the Rule, your program must:

- Identify the kinds of red flags that are relevant to your practice;

- Explain your process for detecting them;

- Describe how you’ll respond to red flags to prevent and mitigate identity theft; and

- Spell out how you’ll keep your program current.

What red flags signal identity theft? There’s no standard checklist. Supplement A to the Red Flags Rule – available at ftc.gov/redflagsrule – sets out some examples, but here are a few warning signs that may be relevant to healthcare providers:

- Suspicious documents. Has a new patient given you identification documents that look altered or forged? Is the photograph or physical description on the ID inconsistent with what the patient looks like? Did the patient give you other documentation inconsistent with what he or she has told you – for example, an inconsistent date of birth or a chronic medical condition not mentioned elsewhere? Under the Red Flags Rule, you may need to ask for additional information from that patient.

- Suspicious personally identifying information. If a patient gives you information that doesn’t match what you’ve learned from other sources, it may be a red flag of identity theft. For example, if the patient gives you a home address, birth date, or Social Security number that doesn’t match information on file or from the insurer, fraud could be afoot.

- Suspicious activities. Is mail returned repeatedly as undeliverable, even though the patient still shows up for appointments? Does a patient complain about receiving a bill for a service that he or she didn’t get? Is there an inconsistency between a physical examination or medical history reported by the patient and the treatment records? These questionable activities may be red flags of identity theft.

- Notices from victims of identity theft, law enforcement authorities, insurers, or others suggesting possible identity theft. Have you received word about identity theft from another source? Cooperation is key. Heed warnings from others that identity theft may be ongoing.

SETTING UP YOUR IDENTITY THEFT PREVENTION PROGRAM

Once you’ve identified the red flags that are relevant to your practice, your program should include the procedures you’ve put in place to detect them in your day-to-day operations. Your program also should describe how you plan to prevent and mitigate identity theft. How will you respond when you spot the red flags of identity theft? For example, if the patient provides a photo ID that appears forged or altered, will you request additional documentation? If you’re notified that an identity thief has run up medical bills using another person’s information, how will you ensure that the medical records are not commingled and that the debt is not charged to the victim? Of course, your response will vary depending on the circumstances and the need to accommodate other legal and ethical obligations – for example, laws and professional responsibilities regarding the provision of routine medical and emergency care services. Finally, your program must consider how you’ll keep it current to address new risks and trends.

No matter how good your program looks on paper, the true test is how it works. According to the Red Flags Rule, your program must be approved by your Board of Directors, or if your organization or practice doesn’t have a Board, by a senior employee. The Board or senior employee may oversee the administration of the program, including approving any important changes, or designate a senior employee to take on these duties. Your program should include information about training your staff and provide a way for you to monitor the work of your service providers – for example, those who manage your patient billing or debt collection operations. The key is to make sure that all members of your staff are familiar with the Rule and your new compliance procedures.

WHAT’S AT STAKE

Although there are no criminal penalties for failing to comply with the Rule, violators may be subject to financial penalties. But even more important, compliance with the Red Flags Rule assures your patients that you’re doing your part to fight identity theft.

Looking for more information about the Red Flags Rule? The FTC has published Fighting Fraud with the Red Flags Rule: A How-To Guide for Business, a plain‑language handbook on developing an Identity Theft Prevention Program. For a free copy of the Guide and for more information about your compliance responsibilities, visit ftc.gov/redflagsrule. For questions about the Rule, email RedFlags@ftc.gov.